And the bells are ringing out

The Pogues ft. Kirsty MacColl, “Fairytale of New York,” If I Should Fall From Grace With God (1988)

Marah, “New York is a Christmas Kind of Town,” A Christmas Kind of Town (2005)

‘Twas the night before Christmas and, as a dozing man slipped into dreams, fresh snow was beginning to fall outside. In the fairytale poem A Visit from Saint Nicholas, written by Clement Clarke Moore, the owner of the country estate that would become the Manhattan neighborhood of Chelsea, the fellow is a kindly patriarch whose sleep is interrupted by a “jolly old elf” who leaves toys for children then evanesces up the chimney. For the Irish singer-songwriter Shane MacGowan, the fairytale begins with the narrator sobering up in a New York Police Department holding cell, and the intruding old man an ailing inmate caterwauling folk songs from the old country.

The fairytale of New York City is the one that immigrants from all over the world have heard for generations. “They’ve got cars big as bars; they’ve got rivers of gold,” is how MacGowan’s duet partner Kirsty MacColl describes what he promised to her of the Big Apple. Their romance is magical to begin with: two beautiful young people kissing in the city streets, dancing until late, and pursuing twin fortunes: “When you first took my hand on a cold Christmas Eve, you promised me Broadway was waiting for me.”

Irish immigration to the United States dates to before the Revolution, but occurred principally — particularly in the case of Irish Catholics —in successive waves during the 19th and 20th centuries. The largest of these was an influx fleeing the potato famine during the late 1840s; close to one million Irish arrived in the United States between 1845 and 1850.

Their influence on New York was profound. It was the nation’s largest city and principle entry point for arrivals from Europe, and many of the newcomers remained in the place they had arrived and exerted the powers available to a close-knit community shaped by ethnic and religious solidarity. Tammany Hall became a feared political machine that dominated the city’s politics, and, under its influence, the Irish and their descendents claimed a disproportionate share of government jobs, especially in the police department. Even during the late 1960s, 42 per cent of New York officers claimed Irish heritage; “If it weren’t for the Irish, there would be no police,” the city’s former commissioner Francis Adams said.

“Fairytale of New York” speaks of an “NYPD choir singing ‘Galway Bay’,” but, somehow, no such institution exists. The closest thing is the Emerald Society — an organization formed within the force to recognize that specific cultural heritage — and its Pipes and Drums Band, members of which appear in the song’s video. There, the participants were filmed singing the theme to the entirely American television show The Mickey Mouse Club because they did not know the more traditional tune the lyric assigns them.

The number of Irish in America waned after it had reached its mid-19th century high point, but their influence did not, and nor did the connection between their island and New York. “In Ireland, like, you’re either dead or in America,” MacGowan told the BBC in a 2005 documentary. “If you’re in America you’re not coming back.”

The New York of “Fairytale” is imbued with this sense of diasporic romanticism. Although it is the story of immigrants worn out by their time in America, it was written by new visitors channeling fiction: MacGowan, with his band The Pogues, had recently visited the United States for the first time and had spent much of that visit on a tour bus watching and re-watching the Sergio Leone Jewish crime epic Once Upon a Time in America. That picture itself is a stylised and fantastic image of America and of the city of New York, in which it is set. The critic Pauline Kael wrote that the director, Italian Sergio Leone:

…isn’t interested in observing the actual world — it probably seems too small and confining. He’s involved in his childhood fixations about movies — stories enlarged, simplified, mythicized. (He only makes epics.) There’s no irony in the title: he uproots American Westerns and gangster pictures and turns them into fairy tales and fantasies.

This Italian director’s movie also has an American Italian actor for a lead in Robert De Niro; like other De Niro films, this one could as easily have been about Italian gangsters. “There’s nothing in the movie to differentiate Jewish crime from Italian crime or any other kind,” Kael said, and quotes a friend: “It wasn’t just that you never had the feeling that they were Jewish — you never had the feeling that they were anything.”

“Fairytale of New York” doesn’t take its story from Once Upon a Time in America — the plot and characters are MacGowan’s own — but Leone’s film is a palimpsest for the song’s drama: MacGowan’s story is about the promise and betrayal of these Irish immigrants’ New York ambitions as mediated through a story about Jewish criminals that was told by Italians and Italian Americans hoping to summon the narrative grandeur of American Hollywood.

Leone’s movie was scored by an Italian too: the composer Ennio Morricone, whose overture for the film hangs like a ghost about Pogues pianist James Fearnley’s introduction in “Fairytale,” which is also an overture and is played before the narrative begins, as if it were accompanying the curtain opening before a Broadway show. The Pogues’ melody is not Morricone’s, apart from perhaps a few stray phrases, but the two tunes share a wistful nostalgia and a lightness of touch that belies the weight of the drama they precede. The connection was deliberate; guitarist Philip Chevron has said “we approached the ‘Fairytale’ intro as if good old Ennio Morricone had arranged it.”

And the song shares the film’s slippery relationship with time and dreams. Once Upon a Time swirls backwards and forwards from an opening that has De Niro’s character slumped in an opium den — the scenes find resonance in the description of MacColl’s character as an “old slut on junk, lying there half dead” from “Fairytale” — while MacGowan’s narrative, which introduces its main sequence with “I turned my face away and dreamed about you,” works as a memory, a dream, and a magical realist summoning of the aspirations and artefacts of the past into the present day: the NYPD choir and the ringing bells could belong to MacGowan’s drunken present or of his more optimistic youth.

But if the New York of “Fairytale” is a place imagined and reimagined through successive layers of fiction, so too is the experience of the real-world immigrants the Pogues invoked; for the Irish in New York, as with other disaporic communities, the threads leading back to their home country are fortified by memory and iterative acts of tradition. The City University of New York’s Martin Burke told the BBC in reference to the song, “The world of ‘Galway Bay,’ and the world of John Ford’s Quiet Man, the world of an imagined Ireland, is very much a diasporic world … And that’s one that’s heavily nostalgic and heavily sentimental — and bang, we’re being hit up against this in the very song, where sentiment means sadness.”

It is that link between the imaginary Irishness of memory and history and the immigrant experience as authentically lived that unerlines this relationship between the New World and the old country. “Every generation of Irish immigrants, large and small, carries with it the character of the Ireland they leave behind,” writes Linda Dowling Almeida in Irish Immigrants in New York City, 1945-1995. “Each generation is distinguished by a variety of influences and issues that in the past have ranged from famine to civil war to inheritance patterns.”

Writing in The Irish Review in 1990, Kieran Keohane described The Pogues approach as “pastiche” deliberately deployed to mediate the immigrant experience, comparing them in their ambivalence to James Joyce. “Their texts are composed of fragments and images, usually drawn from the most ordinary and everyday of experiences,” he writes. “Their work is to a great extent a search for meaningfulness and validation of human existence, and they search for these and find them in the most ordinary of places.”

The sentimental and stereotypical evocations of Irishness on which The Pogues call, says Keohane, addresses the experiences of the:

…hundreds of thousands of lrish emigrants who have left Ireland in the 1980s, and typically end up underemployed or working in the black economy in the metropoli of Europe and North America. It is an experience born of the effects of slippage and displacement, of travelling culture. It is an expression of Irishness on the move; Irishness in London, or New York, or where ever the diaspora are.

And although “Fairytale”’s description of new Irish immigrants swinging on Broadway to Sinatra suggests the 1940s or 1950s — the 1950s being a peak period of Irish immigration in the 20th century — in the postmodern sense to which Koehane alludes, it could also refer to the 1980s. That, too, coincided with an influx of new Irish and, in “Theme from New York, New York,” released in 1980, a signature Sinatra hit.

“Fairytale” is seen fondly as a nouveau and alternative holiday classic for its cynicism and rancor, but its success — on release, it reached number one on the Irish singles charts and number two in the United Kingdom — seems better explained by its sentimentality.

This sentimentality is the diasporic one described by Burke, which formed a backbone to the entire career of the Pogues, who were a band formed in London that combined upbeat punkish sounds with traditional Irish themes and arrangements; the pennywhistle and mandolin of “Fairytale” claim it as belonging to the lineage of the “Galway Bay” and “The Rare Old Mountain Dew,” the folk songs mentioned in the lyrics. “Galway Bay,” for instance, was written by Arthur Colahan, an Irish doctor living in the United Kingdom, and its most popular recording was by Bing Crosby, an American who had a holiday pop hit of his own. (It’s called “White Christmas”; you might have heard of it.) “Galway Bay,” like “Fairytale of New York,” is an Irish song about being away from home: “If you ever go across the sea to Ireland,” it begins. Like with the Pogues’ tune, “Galway Bay” was popular because it evoked a sentimental and exoticized Irishness that could be appreciated by immigrants as well as the general public in their new countries.

But “Fairytale” also has a theatrical sentimentality, which is suited to Christmas, a time of holiday shows and pantomimes. MacGowan has compared his composition to the theater, saying “In operas, if you have a double aria, it’s what the woman does that really matters,” and MacGowan and MacColl form a compelling romantic leading duo, with his craggy and faltering voice matched by her tough-edged rejoinders.

And fitting a good holiday show, the narrative has a warm ending; “I’ve built my dreams around you,” MacGowan says, his voice softening, and where before there had been irony, now there’s joy in the closing words: “the bells are ringing out for Christmas Day.”

Bells ring out as well in Marah’s “New York is a Christmas Kind of Town,” another song about Christmas and New York. Marah is a Philadelphia band, not a New York one, but their rock and roll has a hard-scrabble working-class grit familiar to the entire Eastern seaboard. Their songs are usually steeped in American musical history and the sensations of city life; they have a fondness for opening their compositions with the noise of city bustle — traffic signals, honks, sirens, car alarms, shouts, double-dutch rhymes.

“Christmas Kind of Town,” released on a holiday album the band released in 2005, is one of these compositions; it sets its scene with a woman shouting for a cab, placing New York not just as Christmas kind of town, but also a frantic and chaotic one. It then sets about proving its thesis.

New York is a Christmas kind of town. As the centre of American commerce, it is both symbolically and in practice a dynamic engine of this most capitalistic of Western holidays. But it has also stamped itself on the holiday as it exists in popular culture, from the Chelsea origins of “‘Twas the Night Before Christmas,” as it has become known, to the Tinpan Alley origins of American Songbook Christmas standards like “White Christmas.”

More than that, New York is the home of A Miracle on 34th Street. It is where you can see the Rockefeller Center’s giant, lit-up Christmas tree and dance troupe The Rockettes’ Christmas show. It is where Kevin McCallister got lost at Christmas in Home Alone 2. It is the site of the largest and most squalid of the drunken bar crawl extravaganzas that is SantaCon.

Of all of New York’s Christmas manifestations, it is the tradition of SantaCon to which Marah’s song best belongs, though it tries concertedly to avoid that fate. An uncharacteristically manic and ebullient song for a band whose interests are usually less joyous, its mistake — surely intentional — is in supposing that if New York is a Christmas kind of town, then every single aspect of New York, “from Washington Heights to the Bronx on down,” must also be Christmassy.

“Every subway stop is a jingle-bell hop,” insists singer Dave Bielanko absurdly. “Every taxi-cab is a sleigh/Every icy wind is a long-lost friend to greet you on your way.” By the time he urges “put a Santa hat on your noodle and stick a snowflake on your little red nose” — let alone “every traffic cop is a peppermint drop” — over an absurd and insistent swinging rhythm, he’s come off as an embarrassing and slightly pitiable drunk, like a red-faced fellow in a Santa hat who you wish would leave you alone while you also worry vaguely about how he might be sleeping rough tonight in unforgiving weather.

The whole effect is somewhat unbearable, but it makes a kind of sense: Marah’s forced cheer and unsettling enthusiasm captures something very real about the holiday season, as well as about New York. Even while the Rockefeller tree sparkles, there is still slush to be trudged through, shopping bags to be hauled on to the subway, and police officers collaring drunks and dragging them away to spend Christmas Eve in the drunk tank.

Dancing the céili; singing to trad tunes

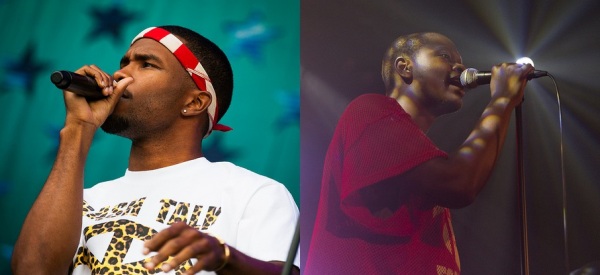

Ed Sheeran and Steve Earle (Photos by NRK P3 and WFUV Public Radio)

Ed Sheeran, “Galway Girl,” ÷ (2017)

Steve Earle, “The Galway Girl,” Transcendental Blues (2000)

Ed Sheeran’s song of a “Galway Girl” begins with their first encounter.

“I met her on Grafton Street right outside of the bar,” he raps in his clumsy folk-troubadour cadence. Grafton Street is not in Galway. It is one of the best-known streets of Dublin. (And there is debate as to whether it has any bars.)

There is no reason a Galway girl might not meet a multi–award-winning English singer-songwriter in a city 200 kilometers from her home, but the geographic indeterminacy sets the tone for this single from ÷, Sheeran’s third album. “Galway Girl” is not about Galway; with its tin whistles and luxuriant pronunciation of “Oi-er-rish,” it is three minutes of Ed Sheeran Doing Ireland, and it makes maximum use of that conceit by cramming in all the shamrocks and shenanigans a top 40 chart hit can handle. (“It’s like a Lucky Charms box suddenly gained sentience,” says Katie Gill at The Singles Jukebox.)

“Galway Girl” was released on St. Patrick’s Day of 2017, and it is a fitting song for a holiday that distills Irishness to green hats and pints of Guinness and then encourages the whole world to celebrate the combination. Sheeran, whose connection to the diaspora is as strong or as tenuous as his Irish grandparents, understands: “There’s 400 million people in the world that say they’re Irish, even if they’re not Irish,” he told The Guardian. “You meet them in America all the time: ‘I’m a quarter Irish and I’m from Donegal’.”

You can imagine those Americans — and Australians and New Zealanders and British and citizens of every other nation in which Irish immigrants found themselves after fleeing famine and unemployment in their home isle — gathered in theme bars on March 17, singing along to The Pogues or Flogging Molly, and challenging one another to down drinks with names like “Irish Car Bomb” (formed by plunging shots of Bailey’s and Jameson in a glass of stout) while they try out their most awkward Liam Neeson impersonations. How would “Galway Girl” go down with them?

“Those type of people are going to fucking love it.”

“Galway Girl” is a cynical song, but it is remarkable for how effective it is in its cynicism. Sheeran claims his label was reluctant to release the song, but his grasp of market segmentation is MBA-canny. He is right: there are a lot of people in the world who would like to enjoy their bare minimum of Irishness to the fullest extent possible, and “Galway Girl” offers exactly the bare minimum of Irishness.

Yet Sheeran is earnest even when he is cynical, and as generic as the Irishisms of “Galway Girl” are, he works hard to realize them. So the lyric mentions the real-life Gaelic phrase (“Nuair is gá dom fháil bhaile, is tú mo réalt eolais”) he has tattooed on his arm, refers to actual traditional folk tunes (“Carrickfergus”), and invokes Van Morrison, the Belfast singer-songwriter Sheeran so admires that he shouts him out again on another ÷ track, “Shape of U.”

Irish Heartbeat, the 1988 album Morrison recorded with traditional Irish band The Chieftains, is a solid reference point for “Galway Girl”; both are attempts by a white pop artist, one who draws from the soul and R&B of African American music, to integrate folk sounds with his contemporary ones. Irish Heartbeat has its highlights, but it is not an uncomplicated triumph for Morrison — and he is a far better soul singer than Sheeran is. Morrison also has a better claim to Irish cultural heritage, though as a man from the north with Scottish and Protestant roots, not an entirely straightforward one. Sheeran, for his part, positions himself as the coloniser: his Galway Girl “plays a fiddle in an Irish band, but she fell in love with an Englishman” — the duo are marked as foundational opposites. But, like Morrison, Sheeran wrote and recorded “Galway Girl” with a traditional — or at least folkish — group; he adapted “Galway Girl” from “Minute 5,” an instrumental by the County Antrim group Beoga.

Sheeran did actually make it to Galway for his song’s video; the Long Walk to which Steve Earle refers is the riverside street in the foreground of this shot.

The American country artist Steve Earle also has a song about a “Galway Girl”; his is from his 2000 album Transcendental Blues. Like Sheeran, Earle is seduced not just by an Irish woman but also by her country’s folk music. “The Galway Girl” is rooted in the same traditional sound Sheeran invokes, but, intriguingly, its banjo and accordion arrangement suggests American bluegrass, a sound closer to home for Earle. His song, which he wrote during a three-month stay in the city, draws an intuitive connection between the folk music of Appalachia and the Old World sounds from which it originates. The link is thematically as well as historically appropriate, underlining Earle’s status as a visitor to Galway who has been felled by the beauty of a local.

Earle’s song also contrasts with Sheeran’s in that it reserves an actual place for the city of Galway in its narrative. He tells of meeting a girl when he “took a stroll on the Old Long Walk” — the Long Walk is an esplanade running along the city side of the River Corrib as it empties into Galway Bay. Striking up conversation, the couple agree to a date down by the Salthill Promenade, a beachfront stretch in the suburbs to the south-west of the city. The Discover Ireland tourist website would endorse the choice; it boasts:

It’s hard to beat Salthill’s location. Situated on the northern inner shore of Galway Bay, the Aran Islands are visible to the right and Galway City, “The City of the Tribes,” to the left. Directly across Galway Bay is the Burren (County Clare) and to the west are the bogs and mountains of Connemara. On a clear day you feel as though you could reach out across the bay and touch the Clare hills though there are also many days when you can’t see them at all.

“I knew right then I’d be taking a whirl around the Salthill Prom with a Galway Girl” (Photo by William Murphy)

But according to Gerry Hanberry, the Galway poet and author of On Raglan Road: Great Irish Love Songs and the Women Who Inspired Them, Earle took some geographic license — his muse was a real woman, but she was not from Galway:

“Everyone in trad circles seemed to know that this was [singer and bodhrán player] Joyce Redmond, who is not from Galway at all,” Hanberry says. “But it wasn’t generally known that she is from Howth, Co Dublin, and her mother is an Aran islander. And it was in Galway that she met Earle — though not on the Old Long Walk of his lyrics.”

Hanberry pinpoints the downtown drag of Quay Street as their meeting point, which would make more sense; it is livelier than the rather lonesome Long Walk.

Quay Street, Galway. The Cafe du Journal on right — it is no longer open — is where Earle is said to have met “The Galway Girl” inspiration Joyce Redmond. (Photo by Megan Eaves)

Wherever it began, Earle’s romance comes to an end in Galway, and he leaves it with the city: “When I woke up, I was all alone/With a broken heart and a ticket home,” he sings. His song would endure in Ireland, however; co-writer Sharon Shannon would re-record it with the Irish artist Mundy and their version became an enduring hit. Earle’s pleading resonated in Galway and beyond: “What’s a fella to do? Her hair was black and her eyes were blue.”

The warmth of your hand and a cold gray sky

Ultravox, Anton Karas, Billy Joel (Photos by Jouni Salo, Wikimedia, Frances Carter)

Ultravox, “Vienna” (Vienna, 1980)

Billy Joel, “Vienna” (The Stranger, 1977)

Anton Karas, “The Third Man Theme” (1949)

I did not enter Vienna under the brightest circumstances: a sodden and gray mid-morning off a train from Budapest I had almost missed. I was visiting for a little less than twenty-four hours, en route to Prague, and the neat houses and steady rain in the central district of Leopoldstadt were dull incentive to venture beyond my hotel room.

If the brevity of this encounter places me poorly to judge the city’s finer points, I am still better equipped than Midge Ure. The frontman of arty new-wave group Ultravox had not set foot in the Austrian capital when he wrote his “Vienna,” in 1980, at age 26, and the city he describes is an imaginary one of impression and intrigue: a distant Briton’s conception of continental glamor in the midst of the Cold War. “There was a decaying elegance about it,” Ure told The Guardian. “In such a crumbling environment, you could easily fall in love. Then you go back to your cold, grey, miserable life in Chiswick.”

Ure was influenced by another Brit: the author and occasional spy Graham Greene, who wrote the novella The Third Man as preparation for his screenplay that would become the 1949 film noir directed by Carol Reed. Reed’s film is set in Vienna in the days after the Second World War had ended, and the city had been divided into four military-occupied zones controlled by the victorious Allied powers in the same manner as Berlin to the north. In this Vienna, the rule of law is hazy and shifting, but the shadows — the film was shot in monochrome — are stark, rendering buildings oblique and figures misshapen. In his novella, which was intended not as a standalone work, but to provide adaptive source material, Greene describes “a smashed dreary city.” Ure’s inspiration was the film, not the novella, but his song imbibed Greene’s prose regardless.

“I never knew Vienna between the wars, and I am too young to remember the old Vienna with its Strauss music and its bogus easy charm,” Greene’s narrator says on the opening page. “To me it is simply a city of undignified ruins which turned that February into great glaciers of snow and ice.” Ruins are no longer what one finds in Vienna, but the Innere Stadt — as I found when I eventually did leave my lodgings to explore downtown — has the pristine majesty of a museum. When Greene writes of the “heavy public buildings and prancing statuary,” he could be talking also about the Vienna of the 21st century; the contemporary united Europe is as far removed from the ruptured continent of the 1940s as was the “old Vienna” of his day.

A cool empty silence: The Kunsthistorisches Museum (Photo by Jonathan Bradley)

Vienna knows both the extent of its majesty and of its irretrievability. It is as if the city located the exact moment during the 19th century, immediately prior to Austria–Hungary’s slow imperial declension, and ensconced itself in Lucite: preserving for eternity that time when a swathe of nationalities across the center of the continent were swept under Habsburg rule; when the Dual Monarchy was an artistic, cultural, industrial, and military power without compare; when Vienna was an intellectual city of lively coffee houses and Johann Strauss. Vienna today is extravagant but orderly; its citizens live modest and well-kept lives amid ancient opulence, not breathing too heavily lest they disturb the exhibits.

“Vienna,” the Ultravox song, has the city’s opulence and the Reed film’s penchant for drama. The synth-pop is concertedly modern, and also, in its baroque extravagance, ensconced in the verve of history. “The music is weaving,” Ure intones, “haunting notes, pizzicato strings,” and he could be referring to an old opera or his own record. The arrangement, which colors electronic pulses with piano runs and orchestral flourishes, achieves a preposterous grandeur: the high-culture artistry of the Western world’s cosmopolitan elite filtered through the best 1980s consumer electronics. Like the ornate palaces and cathedrals of contemporary Vienna, Ultravox’s string augmentation suggests a beauty and refinement and heritage at odds with the tidy immediacy of the current moment. “I wanted to use my classical training,” the keyboardist Billy Currie said in The Guardian interview. “I was keen to do something that sounded like the late-19th-century romantics, like Grieg and Elgar.”

In 2001, the British historian Steven Beller identified the song as part of a re-evaluation of fin-de-siècle Austria, writing in his edited collection Rethinking Vienna 1900:

By the early 1980s Vienna had become distinctly fashionable. Conferences multiplied, pop songs such as Ultravox’s smash hit “Oh Vienna” [sic] were inspired by it, major films such as Bad Timing traded in the new decadent chic of Klimtian ornamental sensuality.

Ure traded on that fashionability, and not in good faith. “I lied to the papers about [the subject] at the time: the Secessionists and Gustav Klimt, whatever,” Ure told Rolling Stone. (Klimt, an art nouveau pioneer, was a leader of the turn-of-the-century Vienna Secessionist movement.) “I didn’t know about any of that stuff. I wrote a song about a holiday romance, but in this very dark, ominous surrounding.”

“That stuff” was the contradiction that gave Ultravox’s song its ambient import. Today’s Vienna seems frozen in its memorialized past, but even at its turn-of-the century height, as it represented Europe’s cultural and artistic vanguard, it was part of an empire that appeared to the rest of the world as an order that had already been consigned to history. As the European powers were organizing themselves according to national allegiances and the principle of self-determination — British, French, German, Russian — Austria–Hungary was an empire that demanded dynastic, not ethnic, fealty. Indeed, one of the overarching foreign policy questions of Emperor Franz Joseph’s monumental reign as head of the Habsburg Monarchy in the second half of the 19th century was whether he would lead a kingdom of the German-speaking peoples or dominate an ethnic conglomeration of Central Europeans.

The conservatism of the Vienna-based Habsburg empire that Franz Joseph ruled — its quashing of the 1848 liberal revolutions and the ensuing demands for constitutional, democratic governance — stood in stark contrast with the subsequent cultural inflorescence that would characterise the capital city. Vienna was simultaneously the focal point of the Habsburg aristocracy and the modernist intelligentsia. But there was a connection: the institutional rebuke to liberalism had pushed the city’s liberals from the despair of politics toward the intellectual possibilities of art and psychology. The introspection was driven in particular by the city’s Jewish population; assailed by the anti-Semitism of the 1880s and 1890s, they turned their attentions and influence towards matters artistic and imaginative.

Ure’s press fabrications notwithstanding, Ultravox’s “Vienna” drew on a century of nostalgia for Habsburg Vienna, of a place cultured, refined, moneyed — and also doomed. That sense of portentous decay that clings to the city, so vivid in Currie’s arrangement, began to accrete almost as soon as the Austria–Hungary Empire had collapsed. Polish historian Adam Kozuchowski, examining the Interwar memory of the Habsburg dynasty, said that the first histories of the period “had to be written in the decline and fall paradigm.” He went on: “It embraced moral and political theory, as well as sentimentalism and nostalgia, bitter criticism, cynicism, and mockery.”

Ure called it a “dark and ominous” surrounding: he did not know the city, but like any good romantic, he understood the aesthetic.

The Plague Column on the Graben, in the Innere Stadt (Photo by tpholland)

Billy Joel’s “Vienna” is also an outsider’s view of a Cold War city, though, as one told by an American, it departs from Ure’s distinctly European vantage. Joel, the Bronx-born son of a Jewish immigrant, allows Europe an émigré’s sentimentality, but his song is inspired directly by a reverse-migration: Joel’s father returned to the continent and made a home in Vienna.

A stately ballad, Joel’s “Vienna” contrasts the hustle of American life with the order of the old world; Joel channelled the German composer Kurt Weill even while he filled out the song’s middle section with an accordion solo that approximates continental folk culture in caricature. “A middle-European, kinky decadent thing,” he called it in a live question-and-answer session included in his The Complete Hits Collection 1973–1997 box set, but it also has the vernacular jazz flourishes of the American songbook. This is Europe as remembered by a Long Islander who knows it from his parents’ stories. “Slow down, you crazy child,” Joel’s lyric lectures, a father to a son. “Where’s the fire; what’s the hurry about?” As it does for Ure, Vienna exists for Joel as an abstract, but Joel sees the city as a totem of continuity: an enduring point of origin that connects the transience of the contemporary moment with a deeper ancestral history.

As a Jew, the irony of locating in Vienna a refuge of stability was not lost on Joel: His father’s newfound home in Europe, he said, “was rather bizarre because he left Germany in the first place because of this guy named Hitler and he ends up going to the same place that Hitler hung out all those years.” Before the Holocaust, Vienna was a Jewish cultural center, with Leopoldstadt — the district in which I stayed — a focal point for the community. Befitting the homage to Weill as well as to his father, Joel’s imagined old Austria is a romantic one of convivial gathering and cross-cultural commingling, but it is shorn of the prejudice and hostility assailing Viennese Jews in the late Habsburg and interwar periods.

Fin de siècle Vienna (Photo via Library of Congress)

As such, even as Joel’s arrangement bends towards nostalgia, its pleasance was more contemporary. It is the Vienna of The Third Man, and not the Habsburgs, albeit one recovered from its postbellum, pre–Marshall Plan deprivation: a non-aligned territory in central Europe secluded from the Cold War. Officially neutral and independent as of 1955, the new liberal democratic republic of Austria was a Western nation not of the West, a free and liminal space between geopolitical rivals. “It’s so romantic on the borderline,” Joel sang, thrusting Austria’s carefully demarcated diplomatic status into the less contested bounds of memory.

Ultravox and Billy Joel spoke of a Vienna that they knew better through film and family than from direct experience, and their songs say more about how the city exists in the international imagination than in day-to-day life. But, in 1950, a song of Vienna spent eleven unlikely weeks at number one in the United States: the instrumental theme music for The Third Man.

The Third Man was written and directed by Englishmen and starred Americans Orson Welles and Joseph Cotten, but it was scored by Anton Karas, an Austrian who used Austrian sounds. Karas got the job when Reed, the director, retired to a suburban wine bar with members of the movie’s cast and crew after a shoot. Wine bars are fixtures of the Viennese cultural landscape; known as “heurigen,” they offer space for local vintners to sell the current year’s crop, and are concentrated particularly in Döbling, the wine-growing district to the north of the city.*

A Vienna heuriger (Photo by Bonnie Ann Cain-Wood)

As well as their food and drink, heurigen are known for their music, and on the occasion of Reed’s visit, Karas and his zither were the evening’s entertainment. Reed decided Karas’s music would be ideal for his film, and, thanks to impromptu interpretation from other patrons of the establishment, Karas (who spoke no English), was made to understand what Reed (who spoke no German) wanted.

Karas would write an original composition for the theme song while on studio-imposed exile in London, but he did not like to play it: it was more complex and less popular than the crowd-pleasing traditional fare that earned him tips. Nonetheless it shows what Vienna sounded like to the actual Viennese — at least for part of the 20th century and in certain parts of the city. The sound was not the portentousness of Ultravox or the schmaltz of Joel, but Karas’s lively pizzicato twanging: traditional song that goes well with a drink and is sharp enough to cut through the noise of a crowded bar.

* The success of “The Third Man Theme” would earn Karas enough money to buy his own nobelheuriger — a fancier version of the traditional establishment — in Grinzing’s Döbling neighborhood, the same place he first met Reed. Opening in October of 1953, he called it Weinschenke zum Dritten Mann, after the German translation of the film’s title. It stood at Sieveringer Strasse 173 until its closing in 1966; a website run by Karas’s grandson proudly displays snapshots of luminaries who visited, but American travel writer Temple Fielding was unimpressed, grumbling in 1960:

Der Dritte Mann (“The Third Man”), at Sieveringerstrasse 173, is not — repeat, not — recommended by this Guide, in spite of the featured zither playing of Anton Karas. In attempting to cash in on the film of the same name, Karas built what impresses us as a rash, cornball imitation of the traditional wine garden — and, if we ever saw a joint calculated to fleece innocent lambs, this is it. As a small sample, one of the musicians literally blocked the door, stuck his hand out, and refused to let us leave before we had forked over a fat tip. The suckers from Yokum Hollow might like this trap, but it’s never again for us.

Even celebrity zither players run the risk of losing touch with their roots, I suppose.

You are already in hell

Frank Ocean and Shamir (Photos by Ole Haug and theholygrail)

Shamir, “Vegas” (Ratchet, 2015)

Frank Ocean, “Pyramids” (channel ORANGE, 2012)

At McCarren International Airport in Las Vegas, slot machines line the spaces between departure gates. Temptation beckons visitors to America’s Sin City the moment they exit the aircraft.

It’s not subtle, but Vegas isn’t supposed to be subtle. Vegas isn’t even supposed to be, by the standards of most cities. It lies in a basin in the Mojave Desert and receives 4.2 inches of rain in a year; average temperatures in July and August peak above 100 degrees Fahrenheit. Founded in 1905 alongside the Union Pacific Railroad line, the national census recorded a quarter century later that a population of little more than five thousand was prepared to live in this cauldron. The following year, the city legalized casino gaming and, for good measure, relaxed its residency requirements for divorce. By 2010, 1.9 million people would call the metropolitan area home.

McCarren International Airport (Photo by Martin Douglamas)

Yet Las Vegas’s identity is as a destination diametrically opposed to the idea of home. “What happens here stays here,” is how a 2003 advertising campaign pitched the city; the agency behind the campaign explained its thought process thus:

The emotional bond between Las Vegas and its customers was freedom. Freedom on two levels. Freedom to do things, see things, eat things, wear things, feel things. In short, the freedom to be someone we couldn’t be at home. And freedom from whatever we wanted to leave behind in our daily lives. Just thinking about Vegas made the bad stuff go away.

Yet what can this liberating possibility hold for the two million people for whom “Las Vegas” and “home” are not separable? “If you’re living in the city, oh, you are already in hell,” sings North Las Vegas native Shamir in “Vegas,” the opening track on his 2015 Ratchet album. But even damned, he’s ambivalent: “The city’s all right; at least night.” In other iterations of the hook, he substitutes “sin” for “city”: the two might be equivalent.

“What is it like to live in Las Vegas?” Rookie Mag’s Amy Rose asked of the singer. “It’s not what people typically think about it,” he told her.

It’s very middle America, but on the West Coast. Las Vegas is by no means a city. It’s just literally the Strip, and the Strip is maybe about a three-mile radius. Everything else is just dirt. [It’s] literally in the middle of the desert.

The city has just what you need. (Photo by Jim Mullhaupt)

Las Vegas was — and is ever increasingly — a cosmopolitan city, but it’s one situated within a conservative demographic landscape shaped by a white population emigrated from the South, a cowboy resistance to government oversight, and a Mormon minority that sees welfare as a religious responsibility rather than a state one. Only a recent influx of Latino residents has pushed the state from a Republican mainstay in national elections towards a Democratic one, albeit of uncertain reliability. Even Las Vegas’s particular interpretation of excess is a conservative one; it celebrates not the libertine emancipation of San Francisco or New York, but the glittering triumph of commerce over moral stricture.

“If there is a laboratory demonstration of the antagonism between economic and cultural capital, it is Las Vegas,” writes critic Carl Wilson in his Let’s Talk About Love: A Journey to the End of Taste. “A city of such pure commercialism that money is its entertainment, interrupted occasionally by a show. Nowhere else is it so palpable that art can be simply the green kid stepping in to give a brief break to the main fiduciary attraction.”

Wilson concludes that Vegas is “a gaudy prison colony run by a phalanx of showgirls who hold hourly re-education sessions to hammer [him] into feeling insignificant and micro-penised.” It’s a self-conscious realization of the aesthete’s inherent inferiority in an environment where money matters more than cultural cache.

If Las Vegas, then, is a place where “middle-managers, lower-rung executives” (as Wilson characterizes the Celine Dion fans who flock to the city to see their idol perform in her Caesars Palace residency show) can wield power unmediated by cultural demands, where does that leave a black and queer performer like Shamir who, while not oppositional in the punk sense, is prototypically artsy?

“Do you party every day?” is what Shamir says outsiders typically ask of Vegas locals, when, in fact, his lived experience is the opposite. “That’s the hardest part — the fact that there’s nothing to do if you’re under 21.”

Shamir was twenty when Ratchet was released, and “Vegas” has a denuded electric pulse over which his rounded countertenor wanders artlessly, the way kids do when the fun parts of town demand identification for entry. As an earlier Shamir track, “Sometimes a Man” — from his Northtown EP of 2014 — put it, “There was no way to move any faster/Because we stay stuck in one place, with nothing to do.”

In the New Yorker, critic Anwen Crawford explicated the connection between Shamir’s music and his hometown, phenomena simultaneously ordinary and alien:

The pull between celebration and isolation in Shamir’s songs seems as much a result of his environment as of his voice: beyond the hectic revelry of the Las Vegas Strip lies the quietness of suburbia and, beyond that, the desert’s unnerving solitude.

At the center of Las Vegas is hospitality, and those who have the money to demand it. Everything else recedes into the inhospitable, the unknowable, and the unspeakable beyond.

In one of the best known narratives of Sin City hedonism, Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, Hunter S. Thompson found himself in those quiet outskirts within which, decades later, Shamir would grow up. Thompson called North Las Vegas a “mean/scag ghetto,” and “where you go when you’ve fucked up once too often on the Strip, and when you’re not even welcome in the cut-rate downtown places around Casino Center.”

This is Nevada’s answer to East St. Louis — a slum and a graveyard, last stop before permanent exile to Ely or Winnemuca. North Vegas is where you go if you’re a hooker turning forty and the syndicate men on the Strip decide you’re no longer much good for business out there with the high rollers.

The racialized overtones of Thompson’s characteristically extravagant prose shouldn’t be disregarded; particularly for Las Vegas’s black residents, the divide between the city’s public face and the more menial lives of those who keep it running has been stark.

African Americans were first drawn to Nevada in large numbers during the 1940s and 1950s, when jobs with federal defense contractors lured families away from the Jim Crow South. What they found when they arrived was a city that would become known as “the Mississippi of the West.”

“If these Delta migrants’ first impression of Nevada was of the desolation and poverty,” writes Annelise Orleck in Storming Caesars Palace: How Black Mothers Fought Their Own War on Poverty, “their next realization was harsher. Las Vegas was a Jim Crow town — not as violent or oppressive as their Delta hometowns, but every bit as segregated.”

One of Orleck’s subjects, the anti-poverty activist Rosie Seals, recalls her first impression of the city in words that appear almost exactly in Shamir’s song: “At least it looks all right at night because of all the bright lights downtown.”

Seals continued, to Orleck:

But then I found out they wasn’t allowing black people to go into those hotels. They wasn’t allowing us to sit or eat in all those pretty restaurants. It was upsetting. I knew back there they didn’t allow blacks to eat in restaurants. But I thought it would be different when I came here.

Instead, it was a town of racially restrictive housing covenants and state-enforced segregation: the city police would close down clubs that catered to a mixed clientele. Blacks found themselves pushed out to the flash-flood plain west of downtown, where housing was in too-short supply and frequently lacked air conditioning or indoor plumbing. In 1949, 80 per cent of houses on the Westside failed to meet federal minimum standards for human habitation.

The casino industry helped entrench discrimination as well. A customer-sensitive enterprise, gaming sought to indulge its patrons’ prejudices, and many of the biggest spenders were white Southerners. Writes Orleck:

Las Vegas was to be a white man’s paradise. Jewish and Italian gangsters, Texan and Oklahoman cowboy hustlers became the lords of these new gambling kingdoms, which were dependent on fantasies of luxury and indulgence. African Americans were pointedly excluded, except as invisible laborers.

When the city desegregated, beginning in 1960, it did so in Vegas fashion and for Vegas reasons: business owners feared demonstrations would disrupt the ever-important gaming industry and integration happened with the acquiescence of organized crime figures: “Tell these people I’m not trying to cut into their business,” said James McMillan, president of the local branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. “All I’m trying to do is make this a cosmopolitan city, and that will make more money for them.”

Capital is ruthless in Las Vegas, and though McMillan won the day, this city remains one in which the workers who manufacture its illusions of pleasure, and the prosodies of the lives they lead as they do, are exiled to the same distant void as the suburbs and the desert. (At Pitchfork, Mike Powell recorded his impression of Shamir’s neighborhood: “an afterthought of residential subdivisions and light-industrial zoning that peters out into the foothills north of town.”)

The New Orleans–via–Los Angeles R&B singer Frank Ocean arrives, like Thompson and so many other tourists, as an interloper delivered from the Interstate-15 freeway, but his proggish funk excursion “Pyramids” is a Vegas story that, like, Shamir’s traverses the mental and geographic outskirts of the city, even as it is drawn toward its iridescent middle.

“Working at the Pyramid tonight”: The Luxor Hotel & Casino (Photo by Davie Dunn)

“Pyramids,” from Ocean’s channel ORANGE album, isn’t necessarily even a Vegas song, though its luxuriant Egyptian iconography distinctly evokes the Luxor, a casino and resort at the south end of the Strip that resembles, preposterously, the Great Pyramid of Giza, replete with replica Sphinx out the front. So too does its narrative of service work that could be sex work. “Got your girl working for me/Hit the strip and my bills paid,” Ocean half-sings, half-raps. Bulging EDM synths intrude upon the arrangement, dragging it into a clubby haze that, in a city designed to streamline the exchange of money for pleasure, could as easily suggest a ritzy bar as it could a nudie joint.

Prostitution has been permitted in Nevada since the 19th century, and even though local law forbids it in Vegas proper, the city has historically been willing to service sexual vices along with its other hospitalities. The strip to which Ocean refers might be any red light district in America — “I have actual pimps in my family in L.A.,” he told The Guardian — but the Strip in question sounds a lot like the most famous one. “She’s working at the pyramid tonight,” sings Ocean, his unglamorous subject a silent participant in an industry that services decadence to anyone willing to pay.

“Pyramids” is a ten-minute, multi-part suite that begins in Ancient Egypt and so becomes a story of mystical Afrocentrism and imperial decline. When the “black queen Cleopatra” is stolen from her throne, she is robbed from an opulence of diamonds and gold, in which wealth is so ingrained that it follows the monarch herself — the “jewel of Africa” who has “skin like bronze” and “hair like cashmere.”

The expropriation collapses the millennia separating the ancient world and the present day; it could be at the hands of slave-traders or a mere rival Casanova. Either way, Cleopatra has become one of the city’s many laborers exiled to its forgotten edges.

In the present day, Ocean and Cleopatra begin their day on the tatty margins of luxury. They’re in cut-rate accommodation, not one of the high-end hotels marketed to the tourists — “Big sun coming through the motel blinds” — and she’s getting ready for work, putting on lipstick and high heels. Ocean is struggling to give the appearance of wealth even while broke: he brags specifically of a “top-floor motel suite” and though his car “ain’t got no gas tank,” he’s still outfitted it with a plush interior.

“Pyramids” is people laboring to produce the Las Vegas economy and hoping that their labor will permit them to become a part of the fantasy they’re selling. It might be because Shamir is a local that he can suggest this dichotomy without succumbing to the illusion himself. When he sings “best believe this city has just what you need,” he sounds like a salesman who isn’t too dumb to use his own product.

“His mom works in property management and his aunt works at a hotel,” Powell wrote, “so he understands the tourist’s dream and the local’s hustle.” But Shamir’s “Vegas” is ultimately neither; as Powell went on, “Mostly, though, he likes to stay home with his needles and his yarn and play records.”

Here on the neon-lit edges of civilization, pleasure erodes into boredom and then into desert. The pyramid glows in the distance. You are already in hell.

Either insane or dead

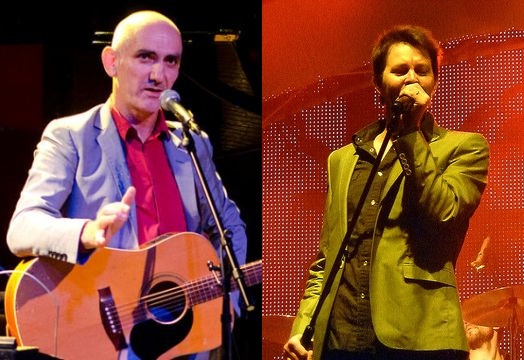

Paul Kelly and Bernard Fanning (Photos by Tim Pierce and fresnel_chick)

Paul Kelly, “Adelaide,” Post (1985) and Gossip (1986)

Powderfinger, “Hindley Street,” Internationalist (1998)

Paul Kelly’s “Adelaide” exists in two forms, one a negative of the other. The song is, alternately, about a boy burying his father or the story of a young man realising he is too big for his small city. It’s a song about leaving and returning, evoking in its two editions a penumbra that is each of these at once.

Initially released credited solely to Kelly on his 1985 album Post, the song would become better known after it had been re-recorded with the Coloured Girls for the 1986 double LP Gossip.

The Gossip version is celebratory and cocksure — a bit too cocksure, in Kelly’s telling; in his memoir-of-sorts How to Make Gravy, published when he was 55, he attributes much of the song’s perspective on his hometown to youthful arrogance.

Adelaide, the older Kelly writes, was a hot and smoggy place — “stewing in brown soup” — looked down upon by the eastern population centres, but, unbeknownst to the same, cultured and genteel: a wine country comparable to that of France, a quote-unquote “world-class” festival city, the chosen home of cricket’s greatest ever player, and a liberal centre founded not as a convict colony but as an exquisitely planned free settlement that would in 1895 become one of the first places in the world to extend suffrage to women and, in 1972, boast a premier who wore pink hot pants in State Parliament.

This is an old man’s perspective: one the younger Kelly, in his telling, had no time for. “Methinks we proclaim too much, murmured my seventeen-year-old self,” he writes.

I was reading Hermann Hesse, Arthur Rimbaud, Jack Kerouac, Henry Miller. They or their heroes had all fled home. Henry was dancing with taxi girls, raving about art, walking past packed Paris restaurants cold and hungry without a sou in his pocket, fucking himself silly, writing whole pages in praise of the variety of cunts. Hesse’s Goldmund was roaming the world, sucking it and squeezing it, princesses and peasant girls too. Arthur was reinventing poetry and pouring forth manifestos; and Jack, sweet Jack, drunk Jack, was trailing after the “mad ones,” sleeping in boxcars, musing on mountains, and staying up for days on Benzedrine to put it all down, every last drop. Real life was elsewhere. I couldn’t get out of town fast enough.

Kelly begins this account by comparing himself to characters from Tolkein and Homer: “All heroes have to leave home at some stage,” he writes. “I left a city that sits on a plain between round hills and flat sea.”

Adelaide CBD and Kensington Road (Google Maps)

Or as he sang at 30 years of age:

The wisteria on the back veranda is still blooming,

And all the great aunts are either insane or dead.

Kensington Road runs straight for a while before turning;

We lived on the bend, it was there I was raised and fed.

“…in Adelaide,” concludes the verse, the town unfurling as a setting for the most stultifying kind of suburban childhood. Kensington Road does run straight for a while before turning; it is a major thoroughfare heading like an arrow eastward from the city towards the hills until, past the suburbs of Rosslyn Park and Wattle Park, it curls round and nestles into a modest cul-de-sac.

“Kensington Road runs straight for a while before turning.” (Google Street View)

This is a small setting and it would prove too small for Kelly. He bursts out from the regulated narrative, spilling exuberantly over the measured residential lots and present-tense constancy demarcating the introductory lines. A brash young man by the time he reaches the song’s bridge, and now fatherless, he takes in his home city. “I own this town,” he crows, and, positioning himself physically alongside city forefather, William Light, he discovers that he’s already grander than his birthplace.

“I spilled my wine at the bottom of the statue of Colonel Light,” he cries seedily, a libertine boozing the local produce away in a posh neighbourhood’s park. “This is my town!” — claiming it and disavowing it all at once.

“I spilled my wine at the bottom of the statue of Colonel Light.” (Photo by Jonathan Bradley)

Adelaide genuinely does celebrate Light, a British military officer who planned the city’s layout. “Light’s Vision,” as it is acclaimed, is a grid one mile square set off from the Torrens River and surrounded by parkland, presciently anticipating the City Beautiful and Garden City movements of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Light’s plan was controversial at the time — the first governor of South Australia John Hindmarsh in particular thought it was situated too far from a harbour — but this enmity would dissipate. A lieutenant governor of South Australia, Samuel Way, captured the prevailing sense of civic pride when he said, in 1905:

Where in the wide world will you find a city better planned than Adelaide? Adelaide with its broad streets and its squares and its Park Lands — 2,300 acres in extent — a grand inheritance of the citizens for all time. The choice and laying out of the site of the City of Adelaide was an effort of genius.

Light’s Plan (History SA)

At the base of the statue honouring Light’s contribution to the city is inscribed an extract from the surveyor’s journal, his words magnificently arrogant:

The reasons that led me to fix Adelaide where it is I do not expect to be generally understood or calmly judged of at present. My enemies however, by disputing their validity in every particular, have done me the good service of fixing the whole of the responsibility upon me. I am perfectly willing to bear it, and I leave it to posterity and not to them, to decide whether I am entitled to praise or to blame.

The statue stands on Montefiore Hill, overlooking the skyline on the other side of North Terrace; the view was better before a hulking revamp of sports centre Adelaide Oval had inserted itself into the foreground. Yet even from this locally hallowed ground, Kelly can tell he’s outgrown his roots, disavowing them as he gazes at the horizon. There is too little excitement here for a young man: “Find me a bar or a girl or guitar; where do you go on a Saturday night?”

“This is my town”: Adelaide skyline from Colonel Light statue (Photo by Jonathan Bradley)

“The streets are so wide; everybody’s inside” is another of his indictments, and it is true; they are and they are: Adelaide’s landscape, planned for grandeur, achieves a kind of vacant office park congeniality. The Saturday night question resonates, too: even today, the town’s weekend nightlife vacillates between the exclusivity of high-end dining and the quasi-rural bloodthirstiness of downtown Hindley Street after dark. This is the City of Murders as well of the City of Churches: a place from which to get away.

“The streets are so wide”: King William Street, Adelaide (Photo by Jonathan Bradley)

Kelly’s first recording of the song is darker; its sense of stasis is stronger. It includes the triumphal bridge, but only as an afterthought. In this version, played solo on acoustic guitar, “Adelaide” is a song about grief and encroaching death. “Dad’s hands used to shake,” he sings, “But I never knew he was dying.” The “insane or dead” great aunts, “red in the eyes from crying,” are not here gothic icons of suburbia, coloured vivid as the wisteria, but a Greek chorus heralding impending mortality. Kelly was thirteen when his father died, but he sounds older here than when he was stumbling round the great statue of the town’s founder: he is already interring his birthplace. He speaks not as if he were going to leave, but as if he were an older man coming back for a funeral.

But older men still will have a more forgiving perspective. Here’s Kelly’s, written in Gravy:

Of course everything was happening in Adelaide all along, and still is— dark secrets, “dithyrambic cunts,” heroism, heroinism, ecstasy, stoicism, every low and high drama, men with large families cut down in their prime, too soon, too soon — enough for a thousand novels, movies, songs, I never had to leave home at all.

But you don’t know you don’t until you do.

If Paul Kelly’s “Adelaide” is about a city weighing heavily upon a native son, Powderfinger’s “Hindley Street” evokes the mundanity enveloping the newly arrived outsider. It’s a mundanity that Powderfinger valiantly returns.

For frontman Bernard Fanning, “Hindley Street” is only another stop to endure in the grinding schedule of the touring rock’n’roll band. “Why should I complain,” he chides. “Everybody else is overworked and underpaid.” He complains nevertheless.

Hindley Street, Adelaide (Photo by Jonathan Bradley)

Hindley Street is a crowded commercial drag in north-west Adelaide; the places Paul Kelly probably didn’t want to go of a Saturday night are clustered along here: big beer barns and take-out pizza joints. For Fanning, it’s a “gentle winter haze” and a run-down hotel room. It could be anywhere: the downtown is so anonymous that, by verse two, he’s shifted north to Alice Springs: “The Todd Street Mall café is here to save the day.” (Port Adelaide does have a Todd Street, but lacking a mall or proximity to the city, it is unlikely Fanning had that one in mind.)

Hindley Street, Adelaide (Google Maps)

The Powderfinger song is a hungover headache of a thing, crawling full of sand towards the alarums of its chorus. Both “Hindley Street” and “Adelaide” are songs about being desperate to leave a place, but only Kelly’s understands what it is leaving behind. Bernard Fanning checked out of a hotel; Paul Kelly closed the door on an elegant and spacious crypt.

Down in TriBeCa; Fairytales in Nolita

Vanessa Carlton and Jay-Z

Jay-Z – “Empire State of Mind” (The Blueprint 3, 2009)

Vanessa Carlton – “Nolita Fairytale” (Heroes & Thieves, 2007)

Songs about New York — and there are a lot of them — particularly by people who live there, tend to focus on the notion of the city as a jungle; a wild, untamable place that either seduces or destroys the singer, and sometimes does both at the same time. From Nas’ “NY State of Mind,” Stevie Wonder’s “Living in the City,” James Brown’s “Down and Out in New York City,” Interpol’s “NYC,” to the collected works of the Velvet Underground, Blondie, Dipset, Wu-Tang, Talking Heads; all see New York City as a seething, out of control place, a city where danger and possibility are inseparable.

The other type of New York song is that by the tourist, who sees the city as a collection of photo opportunities and dazzling landmarks. Frank Sinatra’s “New York, New York” is one of these, as is Cub’s “New York City.” Many songs, of course, combine these two approaches; think of, for instance Ryan Adams’ “New York, New York,” which couples the romanticism of the tourist with the affection and deeper understanding of the resident.

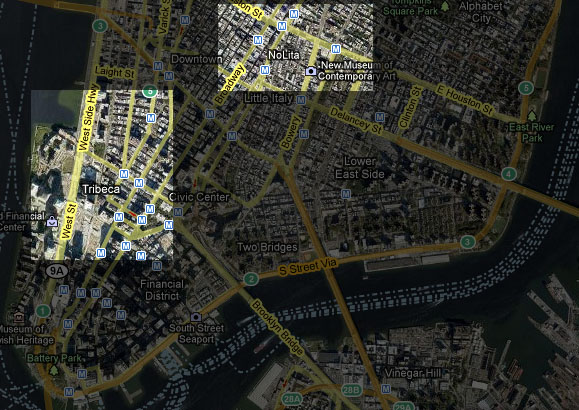

Lower Manhattan

Songs like these do present an accurate picture of New York. The city is indeed a virbant and messy mass of people and communities packed too tightly together and loaded with danger and success at every turn, just as it is a world-renowned landmark that is marvellously inspiring to visit. But Vanessa Carlton’s “Nolita Fairytale” and Jay-Z’s “Empire State of Mind” capture an aspect of the city very rarely commented on in song. The New York in these tunes is the chic, upmarket playground the tourists come for, but for these performers, it’s a chic, upmarket home. Trendy neighborhoods like TriBeCa and Nolita, both in Lower Manhattan, are expensive to live in at all and even more expensive if you want reasonable conditions and a semblance of privacy. But some Manhattanites can afford such luxuries, and they feel much the same sense of attachment to their communities that folks in Greenwich Village or Harlem or Williamsburg do. “Nolita Fairytale” and “Empire State of Mind” exist in the same New York that Sex and the City and Friends do: a city with everything on demand, where there is no better place to be young and upwardly mobile.

I mean, “Nolita Fairytale” is a track written, essentially, for Vanessa Carlton to celebrate rent control! Could it be the most bourgeois tune ever committed to tape?

And yet, the song is lovely, and genuinely affecting. It’s built on a clattering rhythm and a gossamer melody befitting a fairytale, and Carlton paints a Nolita, that section of Manhattan island just north of Little Italy, where she can “walk the streets with a song in [her] head,” skip a fashion show in favor of a visit to Australian café Ruby’s (New York Mag approves) and live in an apartment where she spends her time with her “toes on [her] pup at the foot of the bed.” Carlton bursts with an enviable, irresistible contentment; she really is relating a fairytale, and if this is what life in Nolita is like for her, she is truly lucky.

But it’s not unrelatable either. It’s not the dramatic, excitement-stuffed lifestyle of other tunes about moving to a big city, but I recognize the feeling. I spent a lot of my life in a small regional center, and when I moved to the biggest city in my country, there were times when the range of cosmopolitan restaurants and trendy streets seemed fairytale-like. It’s easy to be cynical about the zest the young and educated feel for that collection of inner urban amenities that fit broadly under the umbrella term “culture,” but that doesn’t mean there is not a genuine joy to be derived from them.

The take on “Nolita Fairytale” in the following video is not as good as the recorded version — Carlton performs it live in her apartment, and is unable to reproduce the percussive hook central to the song’s appeal — but it does provide a glimpse of the tidy, sunlit streets she is celebrating.

One of the better tracks on Jay-Z’s new album, The Blueprint 3, has a similar sense of low key contentment that can only come from having so much money he can afford not to be boasting about it. It’s a bit of a change for the rapper who, in the mid to late ’90s, with Puff Daddy and the Notorious B.I.G., helped usher in an era of rappers ostentatiously flaunting their wealth. “Empire State of Mind” doesn’t have the big money gaudiness of Jay’s 1999 hit “Big Pimpin‘”; in fact, it almost sounds classy. The beat bumps with traditionalist-style sampled boom-bap drums, but the smooth piano and restrained synth blips, along with Jay’s relaxed flow and Alicia Keys’ refined singing on the hook make this something approaching dinner party music. It’s nice, and Jay’s reached the point in his career where he can make nice music without sacrificing his credibility.

TriBeCa Park

The key lyric is the opening couplet: “I’m outta Brooklyn, now I’m down in TriBeCa/Right next to DeNiro.” He then reminds his listeners that he’ll be “hood forever,” but it’s an unnecessary and ultimately unimportant claim. Either way, his life as described in these verses is one split between courtside appearances at Knicks and Nets games and residing in the same highly-desired area (located around the triangle below Canal street) as this collection of luminaries. When his neighborhood watch includes Scarlett Johansson, James Gandolfini, Gisele Bündchen, and Jon Stewart, Hov’s reminders about how much crack he used to sell seem like he’s digging up ancient history.

Sure, there are “eight million stories, “dollar cabs,” and “three dice cee-lo,” but “Empire State of Mind” resonates more vividly during scenes like this one: “Caught up in the in-crowd, now you’re in style/End of the winter gets cold, en vogue, with your skin out.” When Jay-Z tires of the fashion shows, perhaps he’d like to join Vanessa Carlton for dinner at Ruby’s.